« World Without End »

Jesus thrown, threw the centuries. Yes, the violent bear it away. Within the vortex of civilization.

The title comes from the Glory Be, one of the Catholic Mass prayers. It ends with: “As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end.”

The body of Christ is a distortion based on the Isenheim altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald in early 16th century.

Whirled Without End

acrylic on canvas • 30 x 40 inches • 2025

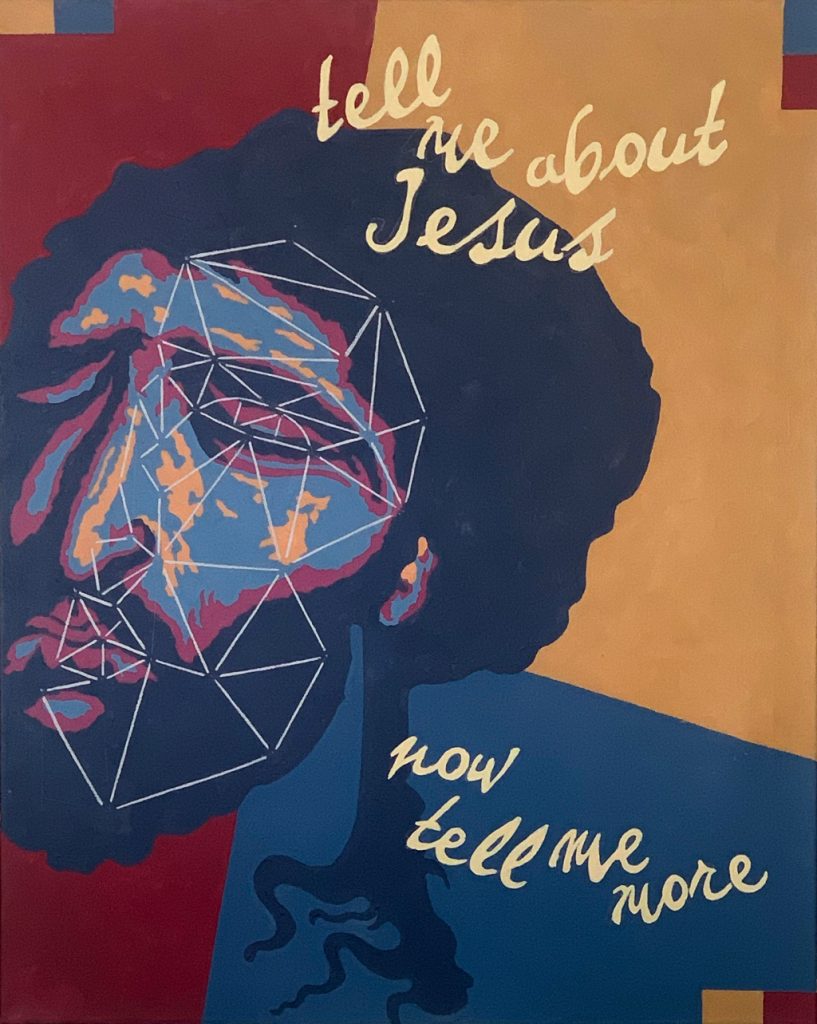

« Tell Me More »

» » notes « «

Way back when, I began making visual art by designing posters. A lot of them. Recently I’ve been thinking of dipping back into that poster style or mode of expression.

This has been a kind of ongoing struggle for me. I have grown up with this preset that paintings should be ‘painterly,’ somehow expressive of the artist’s sensibility and, at the same time, reflective of the world. Paintings belong on the museum or living room wall.

Posters are more about communicating a message, usually to announce an event or sell a product. Traditionally they are more intentional in their choice of visual elements and style of presentation. They are also quick to use the techniques of visual rhetoric to enhance the effectiveness of their message. Posters belong on the street and other venues designed for mass communication.

This is my first attempt at a painting ‘in poster mode.’ We will see where this leads.

Tell Me More

acrylic on canvas • 30 x 24 inches • 2025

« John The Messenger »

» » notes « «

This painting is a bit of an exercise in iconography. There are ways of reading the Bible that pay attention to the myriad of images and symbols that course their way through the text from beginning to end. The dynamic at play is such that an image from one context can shed new light when applied in a different context.

The initial inspiration for this painting came from a somewhat obscure Scripture text. In John 5: 35, Jesus spoke of his mentor, John the Baptist, in this way: “John was a burning and shining light.” This was a reference back to the prophet Elijah, on whom John was modelling his public persona. This was a reference back to the Word of Elijah that “burned like a torch” as written in Sirach chapter 48.

John is dressed in both a priest’s robe and a camel coat as a way of suggesting the inner conflict he may have experienced. He was the son of Zachariah who served as a priest in Temple his whole life. As the son of a priest, John would have been expected to also serve as priest. John’s mother had been barren. In the tradition of other women in the Bible, it is likely that in her prayers for a son she may have promised to dedicate her son to serve God as a Nazarite [one sworn to refrain from alcohol and cutting one’s hair]. John was caught between these two differing demands on his life.

It is possible to see his life choices as attempts to deal with this conflict. He essentially performed the role of priest in reconciling the people to God, but in the wilderness not the Temple.

This painting also suggests that John had affinities with the figure of Moses. Both men 1] were recognized as prophets, 2] led their people through wilderness and water to return them to God, 3] announced the coming of the Chosen One, and 4] sandals were meaningful symbols in their respective contexts.

I presented John as having wings. He has often been depicted this way within the Eastern Orthodox tradition because he was perceived as a messenger from God, ‘angelos,’ an angel.

The image of John the Baptist is modelled on a painting by the 15thC Italian artist, Alvise Vivarini.

My appreciation to James F McGrath, whose book CHRISTMAKER, did much to inspire this painting.

John The Messenger

acrylic on canvas • 40 x 30 inches • 2025

« Baptism At Night »

”Paradoxically, baptism is the washing that makes us unclean, with all the unclean and profane ones of the world.” [Gordon Lathrop, Holy People, p.182] The waters of baptism join the baptized into the entirety of all humanity. It is a full recognition of one’s creaturely vulnerability to deceit, disease, and death. To the earthen clay and mud that clings so fiercely.

I have often wondered whether the ritual of baptism should be performed at night, rather in the bright clear waters of daylight. Only at night, under distant stars, are the waters of baptism dark enough to realize the death of the self that baptism invokes. One is plunged into the depths, without the certainty of returning to the life one once knew. These are dark disarming waters that every creature with breath rightfully fears. Yes, water does give life — the seed in the ground needs moisture. But water can take away life as well.

Baptism At Night

acrylic on canvas • 16 x 20 inches • 2024

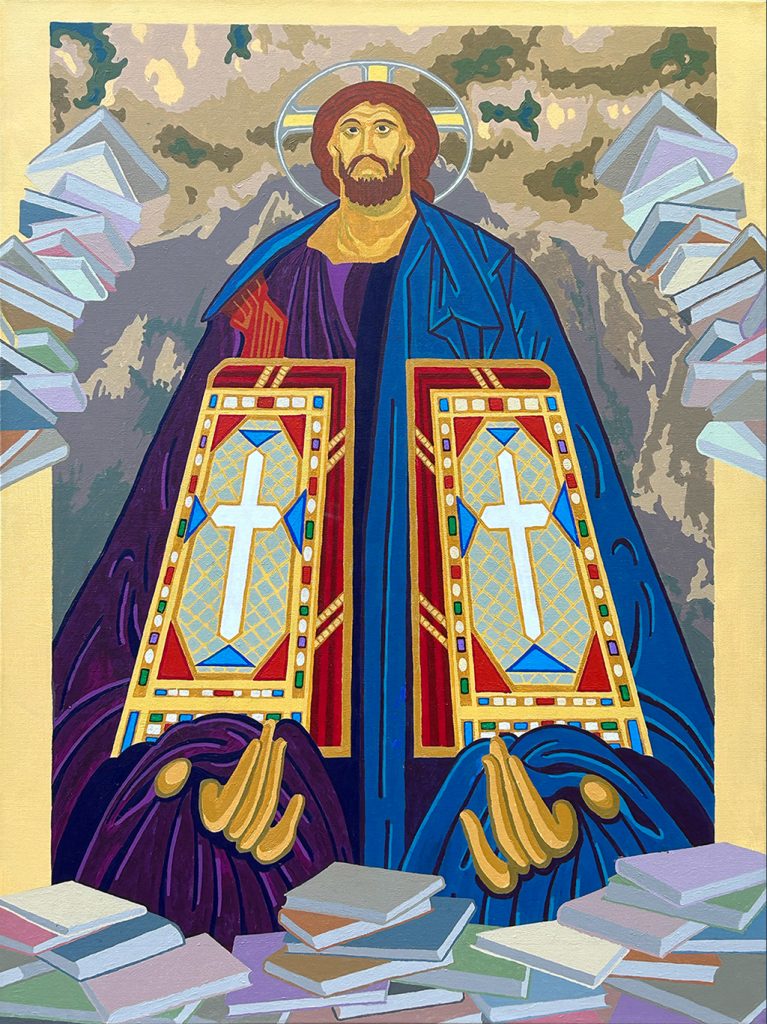

« For As The Law Came Through »

The title For As The Law Came Through is a reference to the Gospel of John, chapter 1, verse 17: “For as the Law came through Moses, truth and grace came through Jesus Christ.”

One of the most common configurations among traditional Christian icons of Jesus is what is known as ‘Christ Pantocrator.’ It is meant to depict Jesus post-resurrection, as sovereign ruler of the cosmos. In his left hand, he cradles an ornamented Bible. His right hand is raised and in a pose that meant to convey blessing.

In this painting, the right hand is no longer bestowing blessing, and instead is displaying a second Bible. The two Bibles positioned side by side bring to mind the two stone tablets on which the Ten Commandments were written. The implication is that within some manifestations of Christianity, it is the Law, not grace and truth that came through Jesus.

For As The Law Came Through

acrylic on canvas • 40 x 30 inches • 2024

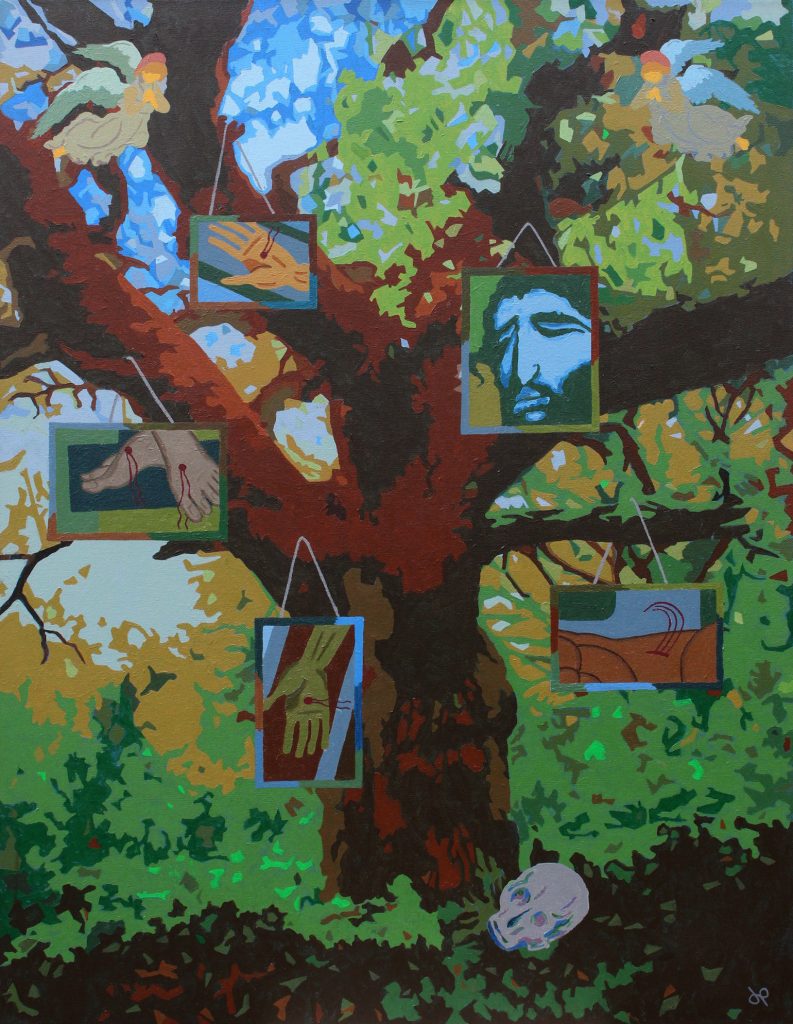

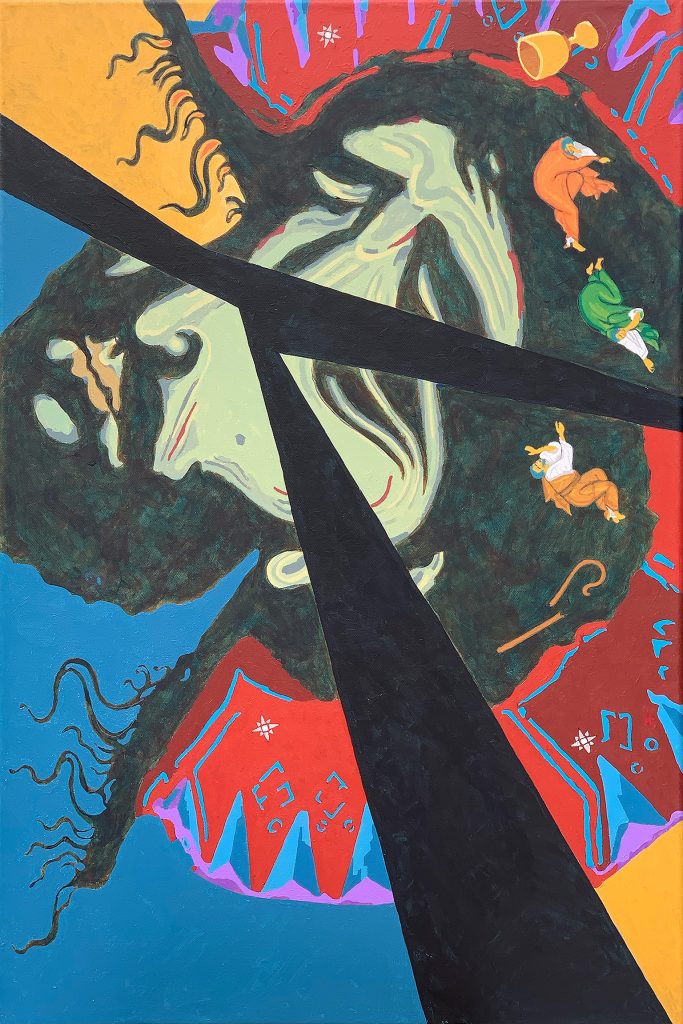

« Christ Hanging »

» » notes « «

This painting draws on several traditions from the history of Christian imagery.

1. The Cross on which Jesus was crucified was referred to as a tree within Scripture itself [Acts 5.30, 10.39, 13.29 and 1 Peter 2.24]. This was picked up in an Old English poem called “The Dream of the Rood,” which imagines the Cross describing its experience of bearing the body of Jesus at his crucifixion.

2. A tradition that viewed the Crucifixion as the event that initiated the process of banishing death and decay, and restoring the world to its original state of goodness at the creation. The tree of the Cross reverses the effect of what happened at the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

3. The hovering angels who are witnessing the scene and Adam’s skull at the foot of the Cross were common in many paintings and altarpieces.

Christ Hanging

acrylic on canvas • 40 x 30 inches • 2024

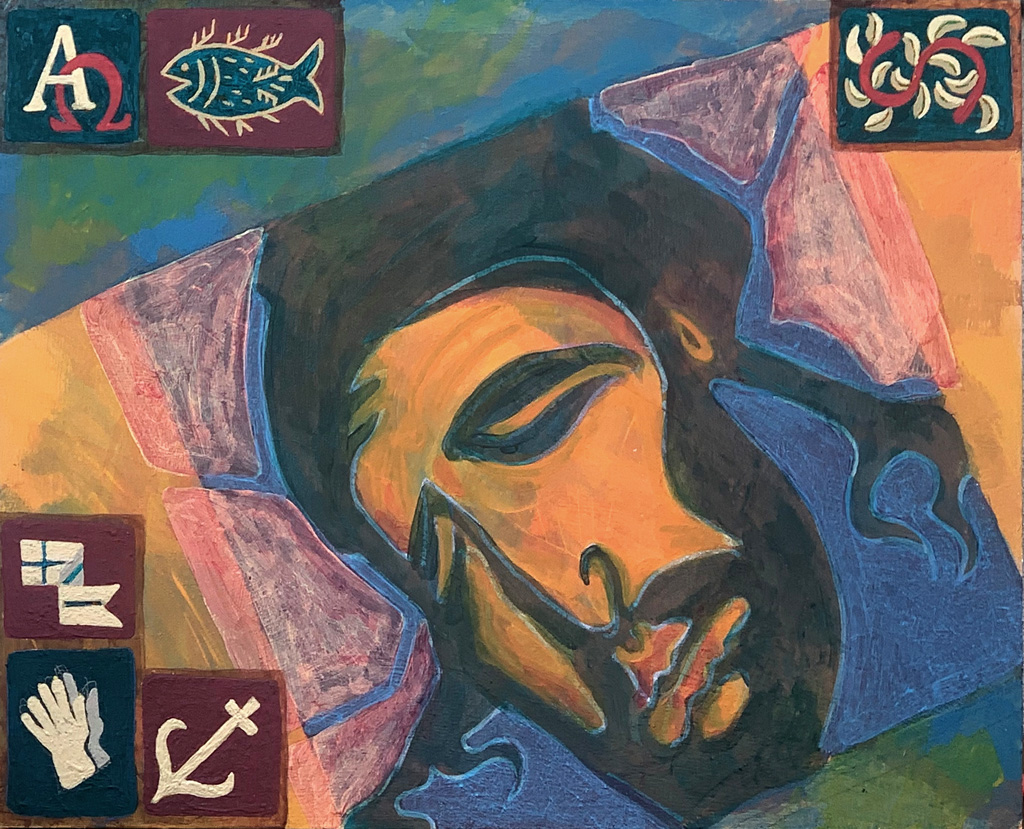

« Yes This Face »

This is an acrylic painting on a birch panel 11 x 14 inches. I am liking this panel idea because it can go on the wall or stand on a shelf, on a table, on a desk, on the floor. You can just pick it up and move it somewhere else to change its presence in your home. I am thinking of doing more and even the possibility of hinging 2 or 3 together. Either larger or smaller.

The face of Christ is based on a 15th century crucifix by the Italian artist Coppola di Marcovaldo. The inset images are of traditional Christian symbols for Christ. Clockwise from upper left they are: Alpha and Omega, the Beginning and the End, Pisces the fish, the true Vine, the Anchor of the soul, praying hands, and Christ’s post-resurrection Victory Banner.

Yes This Face

acrylic on birch panel • 11 x 14 inches • 2024

« My Ways and Your Ways »

This painting works from the text of Isaiah chapter 55 in the Hebrew Bible. The basic composition for this painting came from a photo I took with my phone while working on another painting. The grid structure is the exposed beams in the ceiling of my studio. The white orb is the light that I use when painting.

Isaiah 55 was supposedly addressed to the Jewish people in exile in Babylon. It assured them of God’s intention to return them to their homeland. But it also called them to stop spending their wages on “what fails to satisfy” — their wandering ways within an idolatrous culture that would not return them home. The future with “good things to eat and rich food to enjoy” would be theirs when they “seek their God where He is found, and call to Him where He is near.”

Multiple circuits and paths. Disrupted and intersecting. This one nearly got away from me — so many elements. But I think it found its settling place.

My Ways And Your Ways

acrylic on canvas • 40 x 30 inches • 2023

« Entanglement »

» » notes « «

Quantum Entanglement is a theory in the area of theoretical physics that proposes that multiple units of physical matter can somehow be connected and act as a single unit despite being at a distance from each other.

I find there to be resonances in this theory with various theological understandings surrounding the Incarnation of Jesus. One approach sees Jesus as ‘the heart of creation’ — not as some all-powerful super hero but more as the fullest expression of the goodness of humanity and all creation. This is what I was hoping to point to with this painting.

Entanglement

acrylic on canvas • 28 x 24 inches • 2023

« Ah Poor Jesus »

» » notes « «

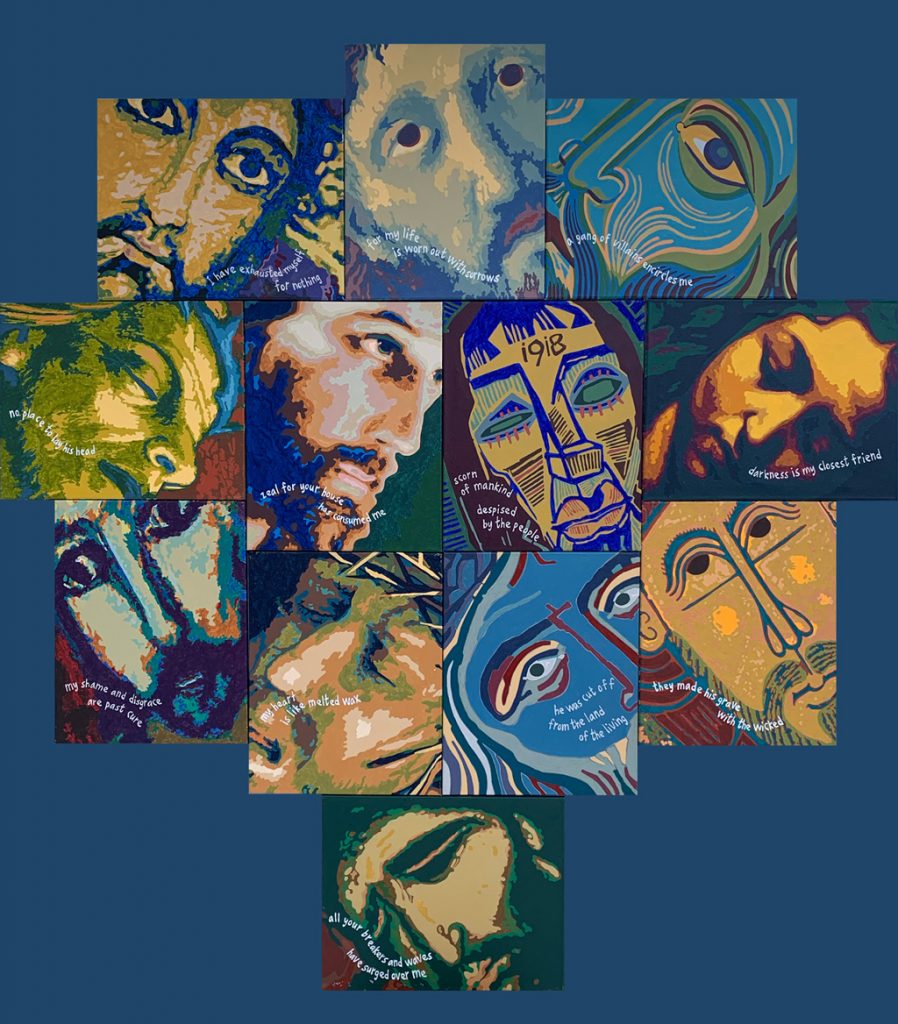

A recent art project finished and installed in our sanctuary for Lent in 2024. AH POOR JESUS is comprised of twelve 16 x 20 inch panels affixed together. Each panel is based on an historical depiction of Christ — from the 12th to the 20th century. Each panel is also inscribed with a text from the Christian Scriptures.

Eight of the texts are from the Psalms, three from Isaiah and one from the Gospel of Luke. There are multiple instances in the Gospels and in Paul where the writer places the words of the Psalmist into the mouth of Jesus. Descriptors of the Suffering Servant were also applied to Jesus in his suffering. This was part of the understanding of the early Christians that Jesus was the fulfillment of traditional messianic expectations.

Below is a listing of the source for each panel

and their accompanying text,

from top to bottom and left to right:

SAN DAMIANO • Italy • 12th century [Isaiah 49.04 • I have exhausted myself for nothing]

PIERRO DELLA FRANCESCA • Italy • 15th century [Psalm 31.10 • for my life is worn out with sorrows]

SICILY • Italy • 12th century [Psalm 22.16 • a gang of villains encircles me]

CARLO CRIVELLI • Italy • 15th century [Luke 9.58 • no place to lay his head]

WARNER SALLMAN • United States • 20th century [Psalm 69.9 • zeal for your house has consumed me]

KARL SCHMIDT-ROTTLUFF • Germany • 20th century [Psalm 22.07 • despised by men and the contempt of the people]

MICHELANGELO CARAVAGGIO • Italy • 17th century [Psalm 88.18 • darkness is my closest friend]

GEORGE ROUAULT • France • 20th century [Psalm 69.19 • my shame and disgrace are past cure]

MATTHIAS GRUNEWALD • Germany• 16th century [Psalm 22.15 • my heart is like melted wax]

SAN MARCO • Italy [Isaiah 53.08 • he was cut off from the land of the living]

CATALAN • Spain • 12th century [Isaiah 53.08 • they made his grave with the wicked]

COPPO DI MARCOVALDO • Italy • 13th century [Psalm 42.08 • all your breakers and waves surged over me]

acrylic on twelve 16 x 20 inch canvases

overall dimensions 76 x 72 inches • 2023

« Exceeding Sorrowful »

“Exceeding sorrowful” are the words from the King James version of the Bible used to describe the emotional state of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane as he confronted the trials and suffering that lay ahead of him. He has just finished partaking in the “the Last Supper,” the Jewish Passover meal celebrating the release of the Jewish people from slavery in Egypt. During this meal with the twelve disciples — the intimate companions who had journeyed with Jesus over the last three years — he announces that one of them will betray him. He tells them that, like the wine of the Passover cup, his blood will be poured out. And that, like the Passover bread, his body will be broken. This meal and time together contained more trauma than celebration.

Then Jesus tells the disciples that he will be “struck down” and that they will all desert him. One by one they protest and declare they would sooner endure prison or even death, rather than disown Jesus.

Jesus then withdraws to the Garden of Gethsemane and takes Peter, James, and John with him — the same three disciples who accompanied him during the Transfiguration. Why does Jesus take any of his disciples with him as he goes off to pray?

One possible answer: there is an affinity to Jesus’ care for his disciples when Jesus interrupted his conversation with Moses and Elijah during the Transfiguration to bend down to his disciples to calm their fears. He has just heard their protestations that even at the risk of prison or death they will not desert him. And yet he knows that though their spirits may be willing, their flesh is indeed weak, and they will fall away and scatter.

Jesus asks the disciples to wait and pray as he goes off to pray alone. This is a relatively simple task compared to the drama and trauma they are about to experience. But they are overcome with sleep and fail to do what Jesus requested. In an indirect way, Jesus is making plain to them how their willing spirits will be overcome by the weakness of their flesh. At the same time, he shows his acceptance of this weakness. He recognizes their “exhaustion from sorrow” (Mark 14.40). Even in the anguish of his utter aloneness, Jesus’ words to them are an encouragement to persevere in prayer.

This painting suggests that the anguish Jesus experienced at Gethsemane was not just about confronting the suffering he was about to endure. It was also about the betrayal and deep isolation he now faced. Jesus was the Good Shepherd who was struck down and lost his sheep [Matthew 26.31: “I will strike the shepherd, and the sheep of the flock will be scattered.” quoting Zechariah 7.13].

The head of Christ is based on a crucifix by Coppo di Marcovaldo [Italian c. 1250]. The figures of Peter, James, and John are based on an icon by Feofan Grek [15th century].

Exceeding Sorrowful

acrylic on canvas • 36 x 24 inches • 2023

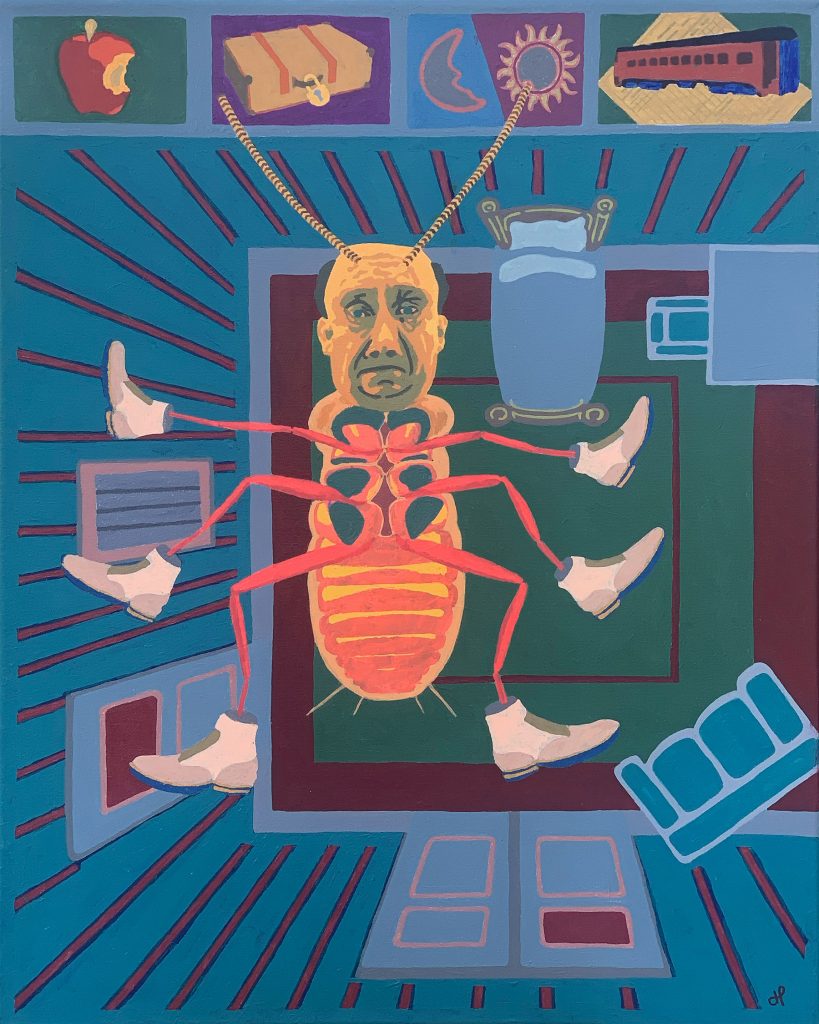

« Coronamorphosis »

This painting was made inside the experience of the COVID lockdown. The imagery is based on a novella, The Metamorphosis, written by Franz Kafka and published in 1915. It tells the story of a young man who works as a traveling salesman while still living with his parents in their apartment. He wakes one morning to find that his body has changed into the body of a large beetle.

Needless to say he finds this to be alarming. How would he dress and get to work? What would his parents think? The routine and confined life that he knew previously had just been unexplainably intensified by many degrees.

He locks himself in his room as he struggles in isolation to find a way forward, to somehow return to the previous normality of his life. This unanticipated crisis exposes all the hidden insecurities, anxieties, and contradictions of his life.

One day you awaken and your world seems irreparably changed and beyond your control. This was the experience of us all during the pandemic.

Coronamorphosis

acrylic on canvas • 30 x 24 inches

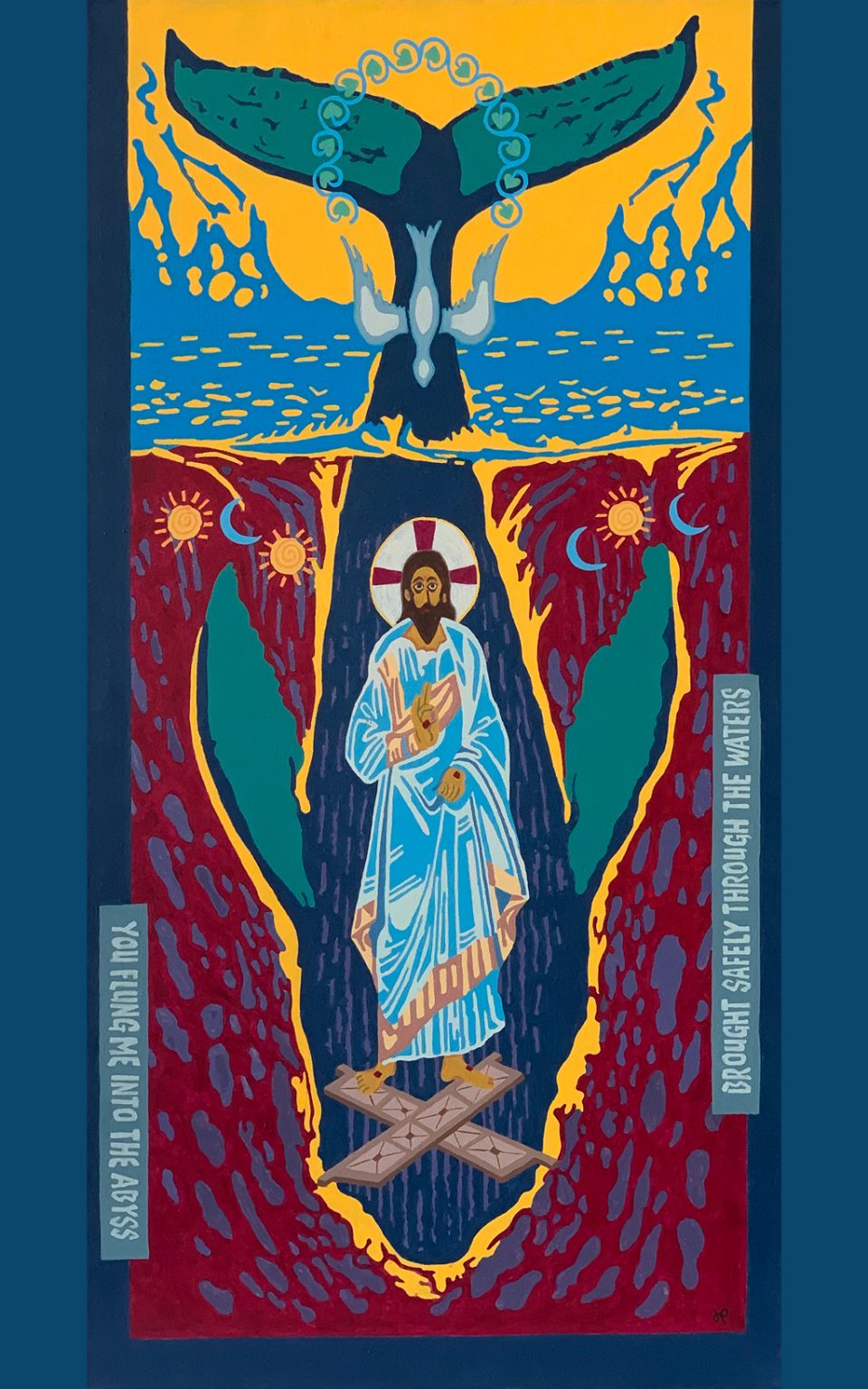

« Three Days and Three Nights »

» » notes « «

In chapter 12 of Matthew’s Gospel, the scribes and Pharisees confronted Jesus and demanded that he give them a sign. Jesus responded with words of indignation:

“This is an evil generation that asks for a sign.”

Jesus then proceeded to say that the only sign this generation would receive would be the sign of Jonah. This sign would be that “as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” By placing Christ in the belly of the whale, Three Days And Three Nights offers an interpretation of this passage.

In similar fashion, after three days God rescued Christ from death ‘in the heart of the earth’ and restored him to life. And the witness and preaching of his resurrection would bring multitudes to repentance.

Beneath Christ’s feet are the broken doors of hell which he destroyed so he could “preach to the spirits in prison” [1 Peter 3:18]. In the Orthodox tradition, this event signals the resurrection of all humanity effected by Christ’s obedience.

Three Days And Three Nights

acrylic on canvas • 48 x 24 inches • 2022

« Blue Christ Waiting Behind the Towels »

» » notes « «

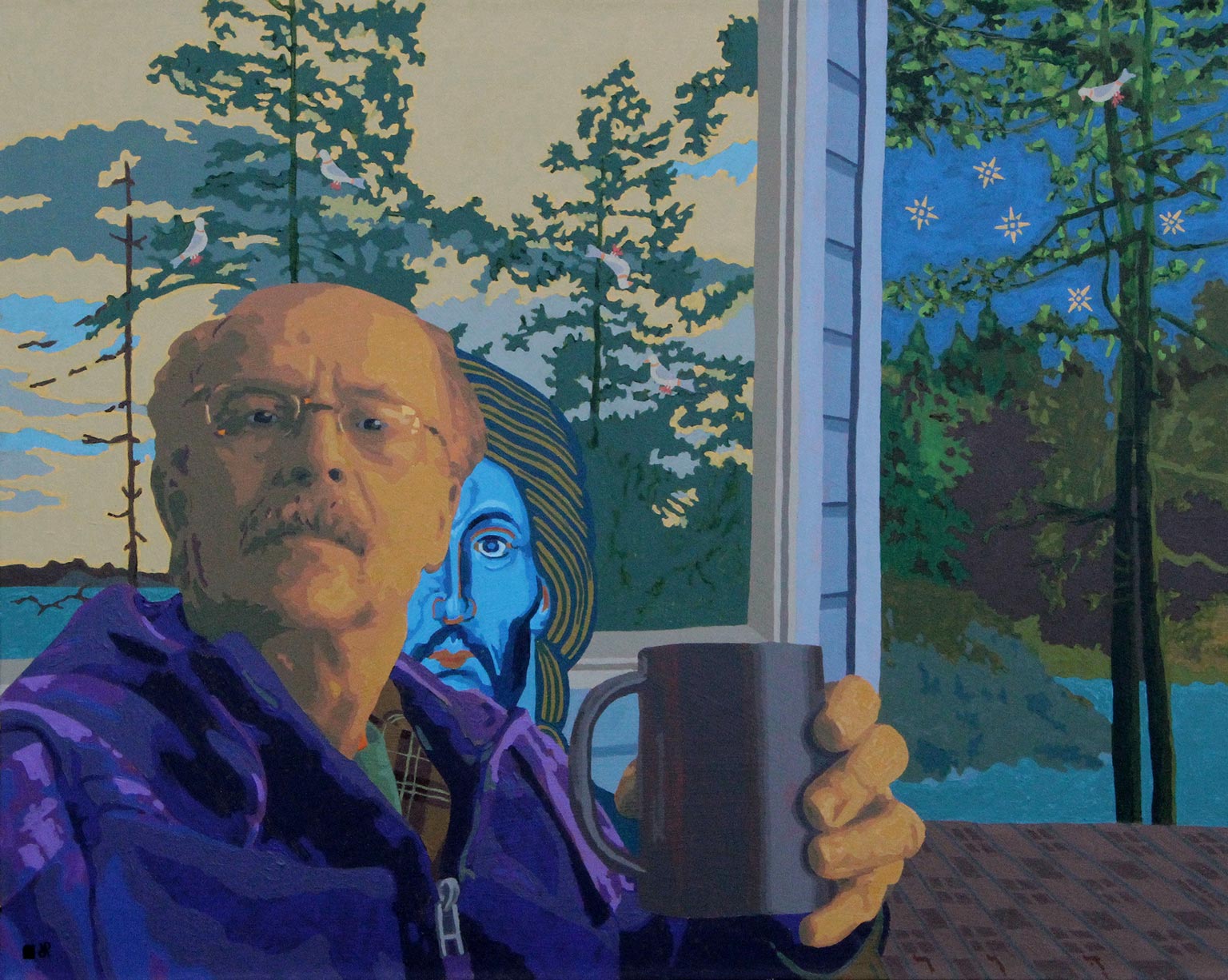

Blue Christ Waiting Behind the Towels is the latest in my Blue Christ series. Taking clues from my recent reading in sacramental theology, this series attempts to explore presentations of the abiding, immanent, enduring presence of Christ in all creation. This we can happily assent to if this places Christ in the splendid beauty and order of the natural world.

However, we seem to be less able to imagine Christ as present and effective in our own immediate lived environments. We are more comfortable with Christ and the whole realm of heaven as being other-worldly — beyond our active engagement. We instead prefer to fashion our own mediating objects — devices, images, and processes to engage our attention.

I think it a most valuable practice to develop ways of imaging the presence of Christ as utterly and lovingly immanent — immediate [without mediation] to our living situations and the face of the other.

Blue Christ Waiting Behind The Towels

acrylic on canvas • 24 x 36 • 2021 inches

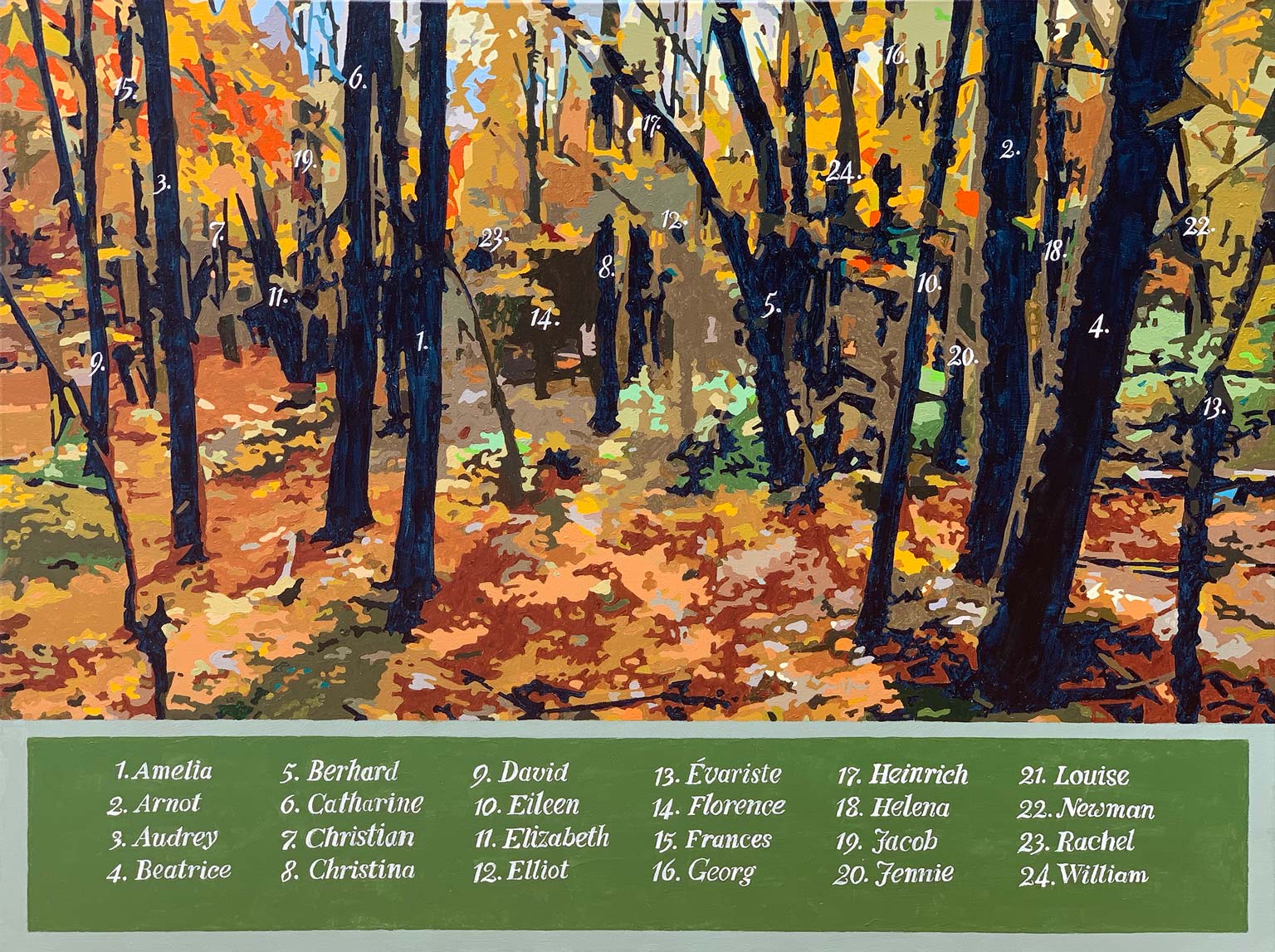

« Next of Kin »

Healthy woodlands are not only necessary for environmental sustainability. They are also vital for sustaining the emotional and spiritual health of — and relationships among — the human inhabitants of this world.

The forest image is based on a photo taken in Scout Valley. The names in the painting are from my own family tree.

Next Of Kin

acrylic on canvas • 30 x 40 • 2021 inches

« But That He Did Not Rise Alone »

Prior to 1000 CE, images of Christ rescuing individuals from Hell in both the Western and Eastern Church were known as images of Resurrection. But gradually from that point forward in the Western Church they were titled The Harrowing of Hell and images of Christ risen from the tomb alone were known as images of Resurrection. This reflects a not insignificant difference in theological perspective.

The title of this work comes from an apocryphal text called the Gospel of Nicodemus. John Crossan has written an entire book on this divergence called Resurrecting Easter.

But That He Did Not Rise Alone

acrylic on canvas • 24 x 48 inches • 2021

8th Catholic Arts Biennial • Verostko Center for the Arts, St Vincent College, Latrobe, Pennsylvania

September 6 to October 29, 2021

« Blue Christ Resting Behind My Brother »

In the last year or so I have been more and more intrigued by the insights of sacramental theology. That all of creation can participate in leading us to participate in the life of God. And that despite all of our concerted efforts, the world is still an enchanted place, in which everything is more connected than we ever imagined, and is being drawn together in grace until God is “all in all.”

The icon image of Christ is blue so that no racial or ethnic group can make sole claim to him. It is an image of Christ, the Logos, the Eternal One. He is taking a Sabbath in the shelter of my brother’s longing heart.

Blue Christ Resting Behind My Brother

acrylic on canvas • 22 x 28 inches • 2021